When one searches for best known journalists, women don't often pop up in first searches.

A journalist that transformed how investigative journalism was done should be one of the top journalists to remember. Unfortunately, this woman, who was a force to be reckoned with, is buried under the otherwise-enabled male journalists.

Nellie Bly (right), born Elizabeth Jane Cochran (later changed to Cochrane) in May 1864, was 16 when she took up the pen. She'd read an article in a Pittsburgh newspaper that lowered the value of women and wrote a furious letter to the editor, who ended up giving her her first job as a journalist at the paper.A Pennsylvania state marker appropriately called Bly "a crusading journalist on Pittsburgh and New York newspapers."

Bly is best known for her flight around the world and her act of going undercover at Blackwell's Island Insane Asylum in New York. While these acts cemented her legacy as a powerful journalist and admirable woman, Bly wrote on more than insane asylums.

Bly started her journalistic career at the Pittsburgh Dispatch in 1885 at the age of 16 after her passionate letter to the editor at the time. Bly, along with what few other women in journalism there were, was restricted to "women's pages," covering society, fashion and topics of typically womanly interest.

The young journalist quickly found herself bored at writing women's pieces. She moved to New York City seeking the adventure of a better story and the nitty-gritty of exposing injustices.

When the New York World, still headed by then-editor Joseph Pulitzer at the time of her employment in 1887, took on Bly, they expected she would stay within the societal confines that a woman should always be protected and kept safe within the office. Bly quickly stunned Pulitzer by pitching adventurous and otherwise dangerous stories.

Her first major pitch was in 1889 when she wanted to prove Jules Verne's book Around the World in 80 Days wrong. When Pulitzer allowed it, Bly went around the world in 72 days, six hours, eleven minutes, and fourteen seconds.

Bly quickly became known to walk and volunteer for dangerous stories.

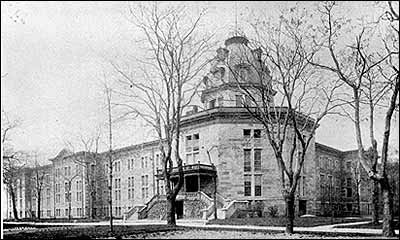

Her most popular and best preserved stories was Pulitzer's idea. He wanted her to investigate the Blackwell's Island Insane Asylum (left) in the East River.

At the time, Blackwell's Island (now Roosevelt Island) was a publicly funded island for isolation. There was a jail and hospital as well as the insane asylum. It was ideal to protect the public from the inhabitants, both from crime and from chronic disease.

But what Bly found was far from humane.

In order to gain access to the insane asylum, Bly had to "act insane."

In the 1860s, asylum admission was broad compared to today's standard. What they considered "insanity" or "madness" was easy to be diagnosed with. Mental health awareness was nonexistent and encompassed mostly unfavorable characteristics. Drunkenness, epilepsy and "idiocy" were considered forms of madness. Mania, melancholy, hysteria, behavioral disabilities and chronic, deteriorating diseases like dementia were signs of insanity.

Bly impersonated someone with amnesia. She wouldn't forget those who were also committed with her. Some were healthy. Others who were healthy weren't native English speakers.

In a series of six exposés, Nellie Bly exposed neglect and abuses the medical staff of the asylum did against the committed persons. The range of abuse went from filthy rooms, cold showers and spoiled food to unmentionable horrors.

Bly later published a personal retelling of her time in the asylum titled Ten Days in a Madhouse. Between the exposés and the book, Bly rose to fame and jumpstarted a more consistent movement for hospital and asylum reform.

Bly was among the first women in the investigative journalism world, then a male-dominate world, to use her journalism to expose injustice and gain justice for victims of the institution. She was one of a handful of women that sparked an era of women stepping into dangers.