|

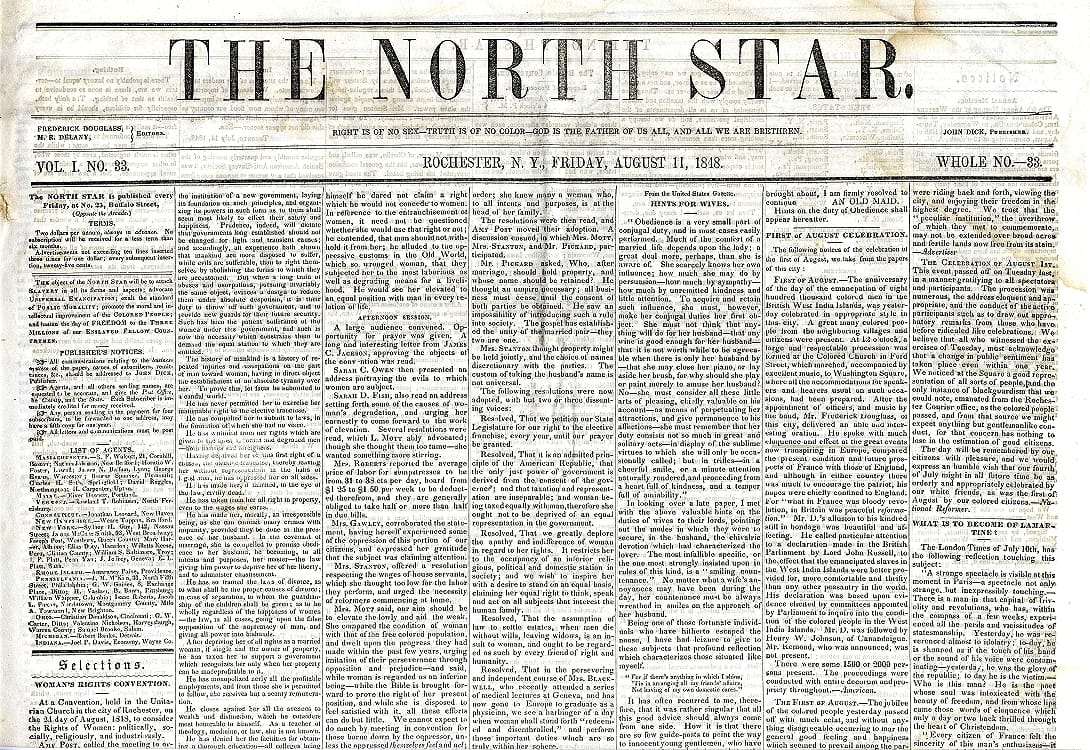

| From The New York Times |

Born in May 1882, in Wakefield, Yorkshire, England, Anne was born to the O'Hare's, both American with Irish ancestry. Her father was a life insurance salesman, whereas her mother was a poet and journalist. It wasn't long before the family moved back to the United States.

The O'Hare's spent most of their time in Ohio. McCormick had two younger sisters by the time her father abandoned the family, which prompted her mother to take them to Cleveland, Ohio. In Cleveland, McCormick worked alongside her mother at what would later be known as the Catholic Universe Bulletin.

McCormick worked as associate editor for the paper while her mother wrote as a columnist and women's section editor. However, when Anne married Francis J. McCormick in 1910, she decided to quit the Bulletin and begin freelancing.

Francis had to regularly travel to and from Europe since he was an engineer, constantly importing large equipment. Most of McCormick's writings went into popular magazines, both for Catholic and non-religious magazines.

She worked as a freelancer to improve her skills. In 1921, she was confident enough in her writing that she wrote to The New York Times managing editor. When he accepted, Anne began sending dispatches.

It wasn't long before McCormick became a regular correspondent for The Times, initially focusing on writing about European life for American readers. She quickly gained respect from both colleagues and readers alike.

McCormick was able gain respect as quickly as she did because she made it a point to gain contacts in every new city she arrived in. She made a point to make contacts in even the government buildings.

Her contacts in Italy gave her the information that McCormick needed to accurately argue Benito Mussolini would successfully rise to power in Italy.

And he did so in 1922.

McCormick's ambitions, accurate reporting, and well-earned trust among colleagues, readers and sources didn't go unrewarded. Her name was on the list of people that interviewed notable figures in history.

Some of the most recognizable figures are from the Second World War:

- Adolph Hitler, Führer (leader) of the National Socialist German Workers’(Nazi) Party

- Benito Mussolini, Italian prime minister (1922–25), "Il Duce" and dictator (1925-1945)

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, 32nd U.S President (1933-1945)

- Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1922–1952), Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (1941–1953).

- Sir Winston Churchill, Conservative Prime Minister (1940-1945 and 1951-1955)

Other notable include Neville Chamberlain, Léon Blum, Gustav Stresemann, Eamon de Valera, Edvard Beneš, and Kurt von Schuschnigg.

It was of note that any male journalist be able to interview the aforementioned people but McCormick was no man. Her ability to adequately interview major political figures and be able to keep her composure only added to her notoriety.

In some of her interviews, McCormick's calm composure allowed her to conflict with an interviewee but not spark as much extreme response or risk of bodily harm. She was able to dance with dangerous questions while avoiding severe and serious repercussions.

McCormick's reputation allowed her to be asked to join the NYT's editorial staff. She joined in 1936.

The following year, she won the 1937 Correspondent Prize for her dispatches and feature articles from Europe from the previous year. She was the first woman to receive a Pulitzer at the Times. This high honor would go on to be her only Pulitzer Prize and a history marker for women at the Times.Despite being a part of the editorial staff and awarded a Pulitzer, McCormick didn't slow down. She continued reporting and being involved in what was becoming an increasingly tense world. She continued through what is now regarded as World War II.

|

The McCormicks, from cleveland.com |

For a couple of those active years, McCormick also acted as the U.S delegate at the UNESCO conferences in 1946 and 1948. UNESCO holds these conferences to determine policies and where the organization should dedicate its work, effectively being a massive exchange of information on a global scale.

Anne O'Hare McCormick worked until her death in New York City on May 29, 1954. The NYT honored her by writing a lengthy obituary in tribute to her extraordinary life.You can read some of her stories below from the New York Times archives (requires subscription):